5. LIFE IN PARIS

1. Studies

An introduction to Western art could only be conceived at the ENSBA, the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This is why, between the 1920s and the beginning of the 1950s, more than a hundred Chinese artists made the same trip to be able to enrol there.

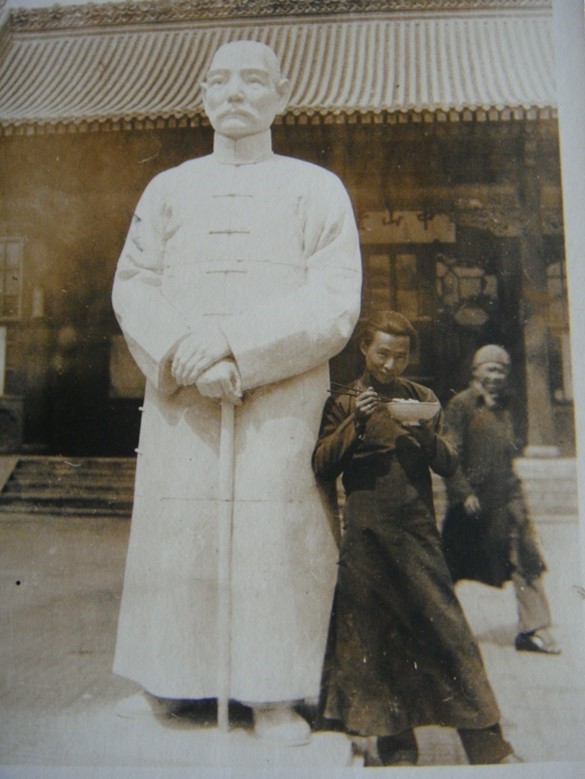

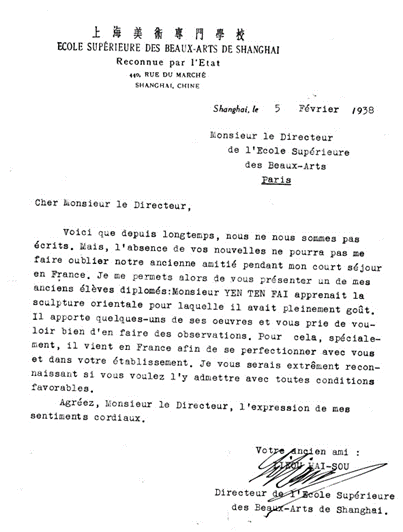

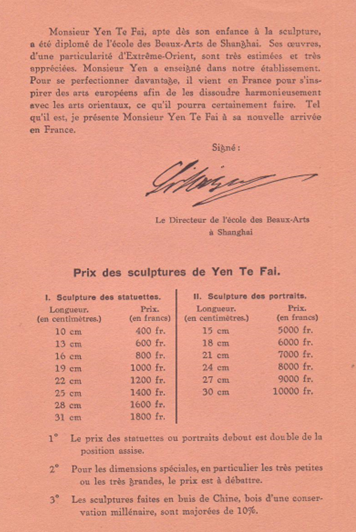

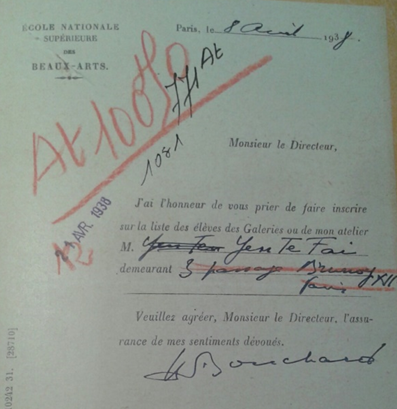

The Director of SAFA Liu Haisu, who had met the sculptor and director of ENSBA Paul Landowski (1875-1961) during his stay in Paris between 1929 and 1931, sent him a letter in French to recommend Yan. On 21 April 1938, the young man was admitted to the studio of Henri Bouchard (1875-1960), a native of Dijon, a renowned sculptor of the time and author of numerous monuments. Liu Haisu also wrote a presentation of his former student, accompanied by the price of his works.

Letter from Liu Haisu to Paul Landowski,

Director of ENSBA

Recommendation by Liu Haisu with

indication of the prices of sculptures by

Yan Dehui

Yan Dehui was a diligent student, as the School’s attendance sheets reveal. Throughout his schooling, several prizes were awarded for his work. There he met Hua Tianyou (1901-1986), who had arrived in France in 1933. Between 1938 and 1943, both attended classes with Bouchard and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière.

Bouchard having left the ENSBA in 1945, from February 1946 Yan enrolled successively in the workshops of Saupique, Gaumont and Jeanniot Gimond, until October 1949, when he left the School for good.

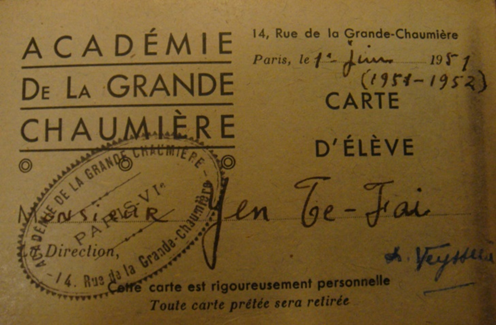

Registration for Henri Bouchard’s workshop

Registration at the Grande Chaumière

ENSBA

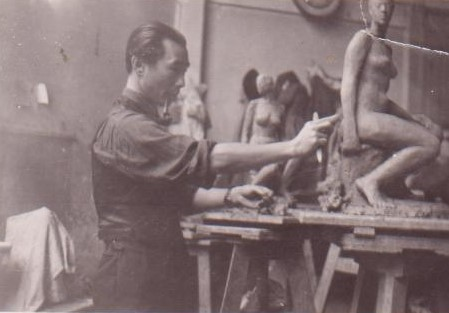

Just as during his training in China, he diversified his production between busts and nudes, between subjects emanating from the Chinese tradition and representations of Western inspiration, between monumental statues and small boxwood subjects.

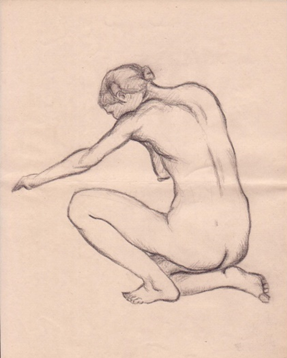

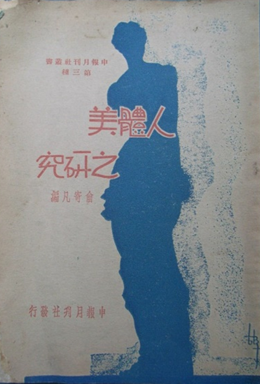

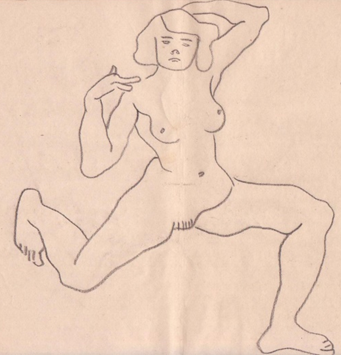

In addition to the art of portraiture, what he perfected above all was the representation of the human body – anatomy lessons, drawing and sculpture from live models, thus breaking with the tradition of classical Chinese sculpture. Other Chinese artists had preceded him in this direction, such as Lin Fengmian, Liu Haisu, Pan Yuliang, Xu Beihong, to name but a few. The representation of the nude in China had constituted, in the course of the 1920s, a subject of artistic quarrel between the proponents of the Chinese tradition and those of modernity.

Yan Dehui, nude study

Collection Yan Dehui,

Yan Dehui, nude study

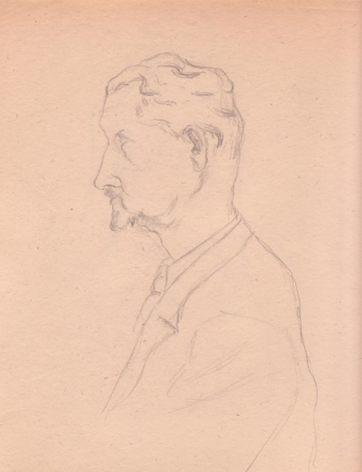

Yan Dehui, portrait of a man, profile

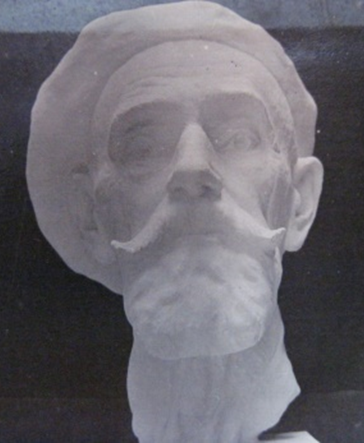

Yan Dehui, plaster sculpture on display

at the Grand Palais during the SNBA Show,

Paris, 1952

This type of academic training marked this generation, even if some later detached themselves from it to turn to abstraction, which corresponded better to the desire for change in post-war Europe.

Yan did not follow this path and remained attached to figurative art, which he also applied to emblematic subjects of Chinese civilization that he focused on representing, such as Confucius and Lin Daiyu.

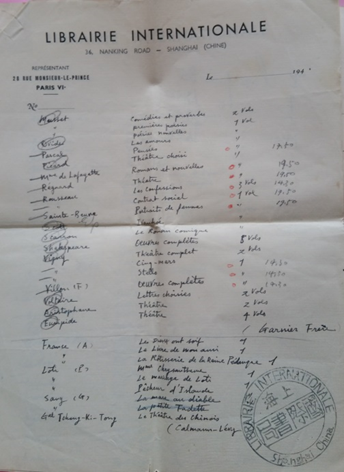

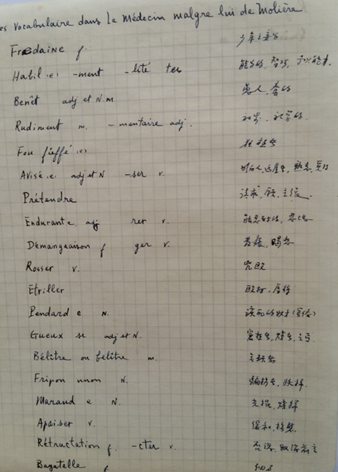

His interest in literature, instilled by his father from an early age, led him to want to discover French culture through classical authors, from whom he bought complete collections. His learning of French was not limited to everyday life and he also wrote long lists of vocabulary taken from plays by Molière or other great writers.

List of books

Vocabulary list

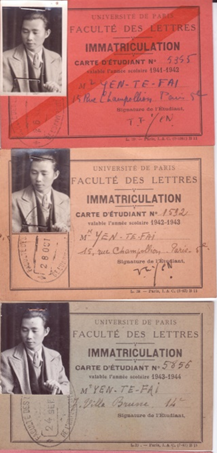

But at the same time, it was also Chinese culture that he wanted to deepen and he enrolled in the Faculty of Letters of the Sorbonne, where he followed the course of Advanced Chinese Studies from 1941 to 1946.

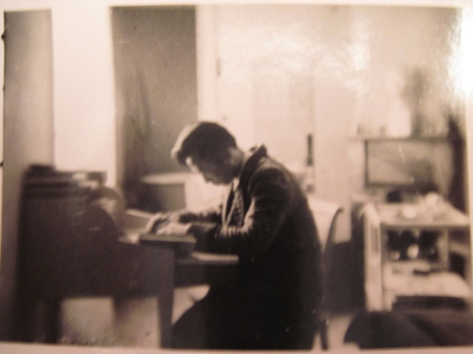

He was extremely studious – in the morning from 8 a.m. to 12 p.m. or in the afternoon from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m., classes at the ENSBA in Henri Bouchard’s studio, and the rest of the time devoted to the study of French, his personal production and the teaching provided by the Sorbonne or the Grande Chaumière.

Study of the French language and culture

Student cards

Faculty of Arts

2. Surviving in Paris during World War II and the Reconstruction years

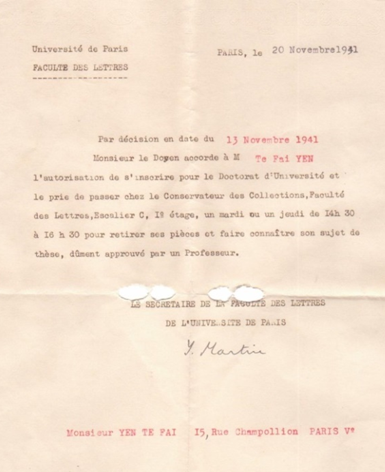

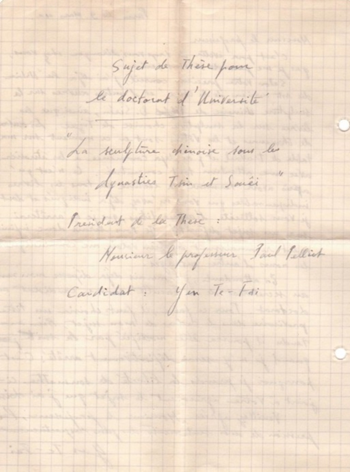

During the war, faced with financial difficulties, Yan had to abandon a thesis project begun in 1941 “Sculpture under the Tsin and Suei Dynasties” (Jin and Sui), under the direction of Paul Pelliot, professor of Chinese literature and art at the Institute of Advanced Chinese Studies of the Sorbonne. He interrupted his studies at the ENSBA between June 1944 and February 1946 because the urgent thing was to try to earn a living in order to survive.

Registration Authorization

to the doctoral thesis, 1941

Thesis subject, March 1942

During this period, Yan moved several times, moving from 123 Boulevard Saint-Michel to 2 Rue Racine, then to 15 Rue Champollion, still in the Latin Quarter. Two other addresses – 6 Rue Victor Cousin and 14 Rue Rambuteau – are also mentioned in administrative archives. For most Chinese artists, paying rent was a problem.

The years of occupation in France were particularly difficult for Chinese artists who lived in extreme poverty. China’s economic situation no longer allowed it to continue the payment of scholarships and everyone had to find their own resources. Mutual aid and solidarity within the community was certainly decisive in helping them overcome the hardships. The Association of Chinese Artists in France, for its part, represented both moral and material support. Some artists were domiciled at the headquarters of the Association, which allowed them to have an effective address.

In 1941 Yan lived for some time in Saint-Chamond in the Loire, where Chinese had worked during the First World War in the Forges and Steelworks of the Navy, specialized in the production of artillery equipment.

In 1942, in support of his application for a scholarship from the National Office of French Universities and Schools, he specified that he had completed a rural civil service internship at the Marly-le-Roi centre and wrote “I would be very happy to go and work in the fields this summer to show my deep gratitude to France, from which I receive a high artistic culture“. But occupied France could not accede to his request.

On the right, Denise Ly-Lebreton, wife of Li Fengbai

On his return to Paris, he was hosted for a time by Li Fengbai, at 14 Rue Furtado Heine, before being officially domiciled in January 1943 at the headquarters of the Association of Chinese Artists in France, at N° 7 Villa Brune in the 14tharrondissement.

Like most of his compatriots, Yan Dehui lived through particularly painful moments during these troubled years, both in France and in China. The letters received from his family report suffering due to war, hunger, various diseases that were spreading, such as measles, plague, scarlet fever, ascariasia and lung diseases… The price of rice was soaring while medicine and money were scarce.

Yan learned of the death of his dear grandmother Fang and, in October 1940, that of his older sister, Yan Zhidao, who left behind five young children. It was her mother, Yan Shenyan, who took care of them, but she herself contracted dengue fever and her health remained fragile for several weeks. Yan’s older brother and younger sister both lost their first child to illness. In France, weakened by deprivation, Yan contracted shingles from which he took a long time to recover.

However, during this period, he continued to work with wood by producing religious sculptures, including the Maitreya Buddha which he sold to Chinese merchants or restaurateurs in order to earn a few pennies to eat, buy carving supplies and pay his rent. His meals often consisted of a stew – a little meat and lots of potatoes – which he ate for several days.

Wood carving

In his garret cluttered with sculptures on the top floor of an old building, he liked to invite his friends over for a frugal meal. All of them found themselves with the joy of exiles who can forget for a time the difficulties of their daily lives to talk about the motherland and the hopes they had for it in a future where they would make their artistic contribution. Joking about the cramped quarters of his accommodation, Yan said that if the ceiling was so low, it was to allow him to catch the moon by extending his arm.

A few letters from his friends mention his generosity – in addition to the money he tried to send to his family according to his financial resources, he gave moral and financial support to those who asked for it.

The lives of Chinese artists, like those of all French people, began to change during the week of August 19-25, 1944, when Paris was liberated after four long years of occupation.

Barricades in the south of Paris, August 1944

In liberated Paris, Yan participated in the general jubilation

If the financial difficulties remained significant, there were not only dark hours. The many photos taken during country walks, outings with friends, festive meals, bear witness to an important social and convivial life, despite the general destitution in ravaged post-war France. The group particularly appreciated picnics around Paris, so practiced during the Belle Epoque and reminiscent of the theme of “Lunch on the Grass” dear to the Impressionists of the previous century.

Then, life gradually improved and the sculptor moved on April 28, 1948 to an artists’ city, at 35 rue de la Tombe-Issoire, in the 14th arrondissement, shortly after the departure for China of Hua Tianyou, who lived at the same address.

Yan Dehui’s lease indicates that it is workshop No. 8, on the ground floor overlooking the courtyard. It remained there until all the tenants were evicted in 1964, when the site was sold to build housing.

Yan Dehui’s last Parisian workshop – 35 Rue de la Tombe-Issoire – 75014 Paris.

This was then transferred to Burgundy

In 1949, he met Louise Lenoir, whom he married four years later.

First Appointments

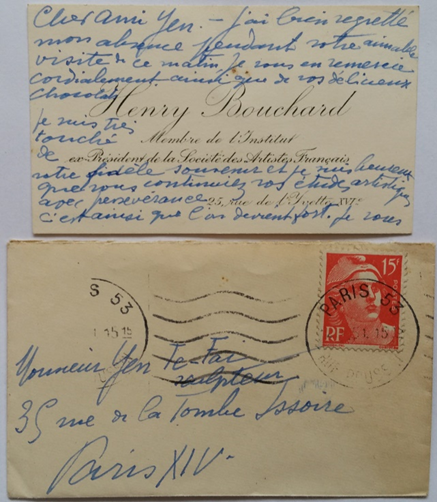

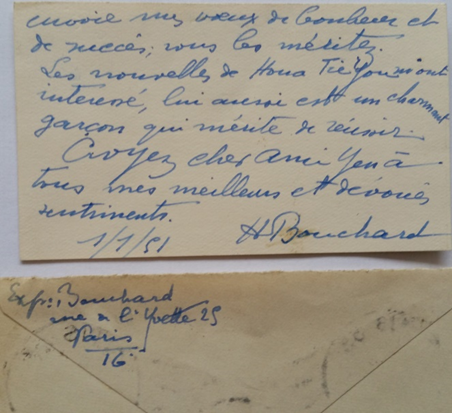

He continued to maintain cordial relations with his former ENSBA teacher, Henri Bouchard, whose last Chinese student he was.

Card written by Bouchard to his former student in 1951

3. Stays in France and trips to Europe

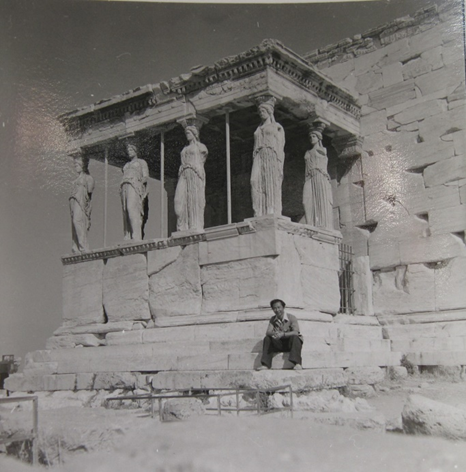

After the war, when their finances allowed it, Chinese artists continued the tradition of the Grand Tour and multiplied their visits to museums, both in France and abroad – Italy, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, Switzerland, Greece, Spain.

During his stay in Greece, Yan did an internship in order to perfect his skills in ancient sculpture and the reproduction of statues. His photos document the life of the time in the places he visited

Stay in Athens, Greece, September 1950

Venice, 1950

He also took many photos during his visits to museums, both in Paris and in the provinces.

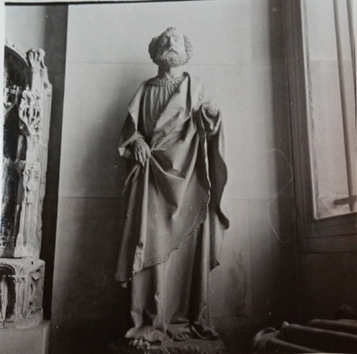

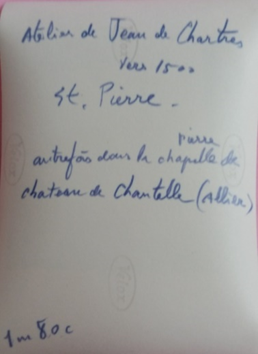

Statue of Saint Peter

At the Château de Chantelle (Allier, France)

These trips were sometimes made with Chinese friends and sometimes with groups of French people.

Trip to Spain in 1951 (still with his camera)

4. Commitment to peace

Born at the beginning of the twentieth century, these Chinese artists have lived in a world of permanent conflict since the first revolution against the Qing dynasty which led to the creation of the Republic of 1912. During the 1920s, a second civil war broke out, during which communist insurrections were relentlessly repressed by the Nationalists. Then came the devastating internal struggles of the warlords, then the involvement in the First World War, the invasion of China by Japan during the Second World War, which came on top of the occupation of a large part of the territory by the Western powers since the nineteenth century, and finally the resumption of the civil war in 1945. which ended with the defeat of the Nationalist Republic of China and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

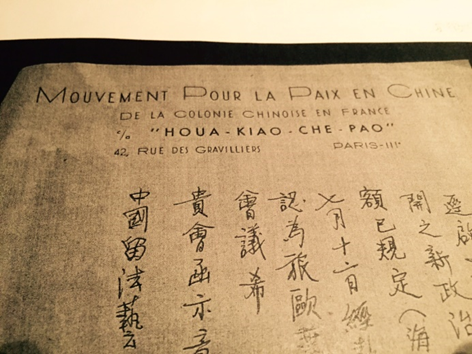

It is not surprising, then, that they wanted to participate in the great world concert in favor of peace after 1945, which saw many associations flourish in order to avoid any future war. The China Peace Movement was founded in 1949. Among its members were Li Fengbai, Yan Dehui, the painter Fang Yong and the nuclear physicist Qian Sanqiang.

These artists, intellectuals and scientists considered that a better understanding between peoples would remove the spectre of war and they saw in art, a universal discipline if ever there was one, the best vector of rapprochement. Aware of their artistic responsibility towards their country, they proposed to be, through this association, the mediators who would allow China and France to get to know and appreciate each other.

In the early 1950s, Yan Dehui sent a letter to the Director of the Education and Culture Committee of the People’s Republic of China. In order to contribute to the development of art in China, he proposed to popularize sculpture and open art to all, first by creating numerous museums in the provinces, then by reproducing masterpieces, both Chinese and foreign, through casts, in order to disseminate them locally and internationally. He offers to carry out this ambitious project and presents a three-step plan to bring it to fruition.